In England, the custom of sending and giving Christmas cards begun in the Nineteenth century, but in countries like Germany or Holland it had already started in the Fifteenth century, with typical spirit tablets representing Saint Nicholas.

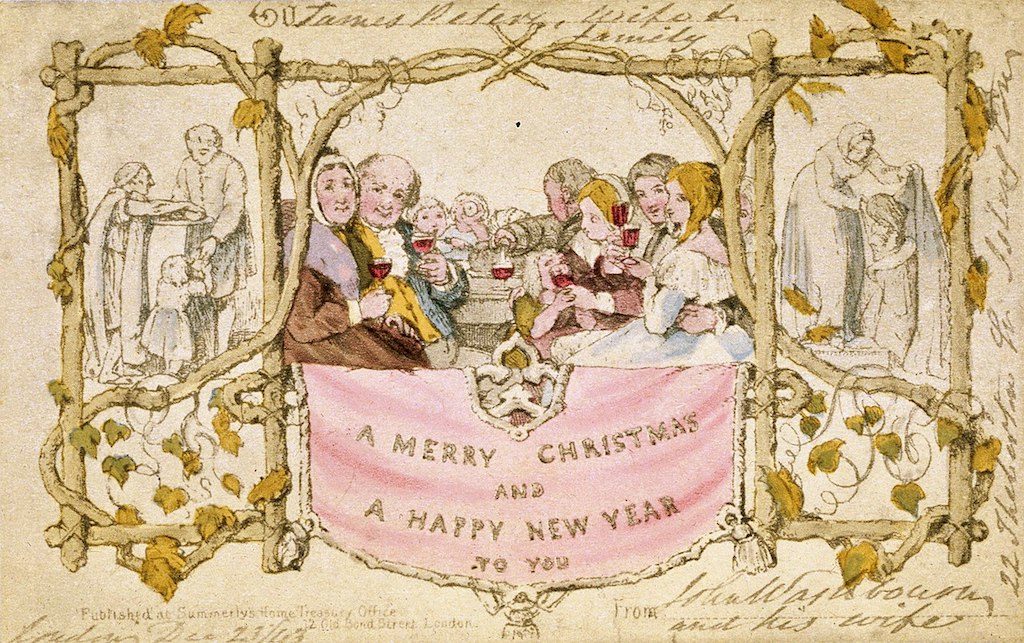

The habit of sending Christmas cards as we know it today though, only spread in 1843. In that year Henry Cole – an eclectic character who contributed to the introduction of the Penny Black stamps and was director at the Victoria & Albert Museum – asked art illustrator Horsley to make a Christmas lithography and print it on cards meant to be sent to Cole’s friends and family for Christmas.

From that moment on, sending Christmas cards with pictures of families celebrating with Christmas pudding and punch, became a typical British tradition and spread all over the world. It is no coincidence that it all happened on the same year when A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens- the book that gave shape to the the modern idea of Christmas celebrations- was published.

Many cards from the middle and late Victorian period illustrated with watercolours and drawings by the Brontës, have been found. It’s hard to say if those pictures were sold to publishers after the Brontës died; what we know for sure is that some of those cards bore the names of Dobbs and De La Rue, two famous publishing houses specialised in greeting cards. Even if this hypothesis has never been confirmed, it would be interesting to know that the Brontës were familiar with the custom of illustrating Christmas cards and would give them to guests or friends long before this tradition became popular. For sure the Brontës were particularly interested in copying pictures from Christmas annuals. Charlotte, for instance, copied from the Christmas annual “Forget-me-not, Atlantic Souvenir”– published by Ackerman in 1830- many images like Woman With Lyre. They’ve also taken inspiration from illustrated albums which included many pictures and articles, but also featured blank areas on some pages for drawing or writing. Not only did the young Brontës love to look at them, they even made some albums themselves filled with watercolour cards and drawings.

These artworks were made together with the stories and the sketches from the tiny handwritten books. The most relevant Christmas work is Madonna and Child, made by Charlotte when she was twenty- pencil on paper, 1835. It is the copy of an engraving by Louis Schalz, which in turn copied it from Madonna of the Fish by Raphael. Virgin Mary’s face, delicate and elongated, is marked by a light chiaroscuro and it’s close to Baby Jesus’s face. The drawing reveals great attention to the anatomy of the faces, especially the eyes (many of Charlotte’s sketches depict eyes). In all probabilities, the author of Jane Eyre started this illustration at Roe Head, and finished it back in Haworth during her Christmas holidays.

However The link boy by Branwell – made in 1836 during his apprenticeship with painter William Robinson- is probably the artwork that better evokes the Christmas atmosphere. The subject of the painting is a boy carrying a lantern. It was probably given to the Heatons of Ponden Hall as a friendship token. Since the Renaissance, “ink boys” carried their lanterns in front of people to light up the darkest alleys in the streets of London and other British cities. They can be often found in Christmas cards from the Nineteenth century.

This might be the copy of a print and it was made by Branwell oil on panel to practice chiaroscuro- we can easily tell that from the strong use of brown, yellow and red. The contrasts and chromatic agreements show Branwell’s initial inexperience. The boy carrying a lantern is wearing a heavy coat; he is ruddy and happy, the lanterns light up his face partly covered by a winter’s hat.

Elena Lago, Art Historian

Cover image: John Callcott Horsley, first Christmas card, 1843, lithogtraphy

If you want to learn more about the Brontës and art, here are some articles you can’t miss: Su Blackwell and Her Delicate Paper Worlds at the Brontë Parsonage Museum- An Article by Elena Lago , Serena Partridge: a delicate embroidery for Charlotte Brontë- An Article by Elena Lago, Lynn Setterington: Sew near – Sew far, An Article by Elena Lago.